Introduction to Redux.

September 15, 2019 - 8 min readHi guys, today is a holiday in Costa Rica, we celebrate our independence and I’ll write and article for the sake of being a free country.

When you’re learning react is possible that you find articles, tutorials and projects using redux, it a widely used library when using react(even though is not particular to it) and solves one of the react biggest questions, How can I share props to non child component?.

That’s when redux comes in handy, based on their docs Redux is a predictable state container for JavaScript apps, it helps us, to share state between the application, in react that means that we can inject that piece of global state, across the whole app, without worrying if the components are attached to each other.

Before starting to dig into the boilerplate, first I would like to talk about the principles, that you should keep in mind when using redux.

- Single source of truth This means that the state of the application should be stored in an object, which we’ll call store

- State is read-only State can only be changed by an action, which is an object that we would talk later on the tutorial.

- Changes are made with pure functions To specify how the state is going to change using the actions, we should use reducers, reducers are pure functions that return new state objects.

For this tutorial we will talk about, actions, action creators, reducers and action types:

An action is a plain javascript object that sends data to the store. they look like this:

{

type: "FETCH_POKEMON_SUCCESS",

payload: ["Bulbasaur", "Squirtle", "Charmander"]

}The action creator is a function that creates actions, they can be easily confused, but just think them as functions that return an action.

An action type normally is how do you want to name your action, remember that an action is an object and basically the action type is the reference for the reducer of the dispatched action.

A reducer describes how the app changes based on the action received, normally a reducer is a switch statement that receives the redux state and the action as the parameters, and it return the state change in a new object(never mutate the existing one).

Now that you know a little bit about the core principles and the basics, we can start talking on how to write it. At the end redux code becomes a boilerplate, once you get used to it, you start writing everything automatically.

Redux file structure is diverse, because the library itself does not specify, how should you organize your code, it has a few guidelines on how to, if you are used to use opinionated frameworks.

I like to use the ducks structure, which differs from the others implementation because it holds all the redux logic in just one file, normally most of the examples that you find are based on a folder structure, where you’re storing your reducers in one folder, your actions in another, the action types in another, and so on. While that is also a good approach as well, I believe that it makes it a little bit harder to know what is happening, specially for beginners. The structure I use(ducks) is something like this:

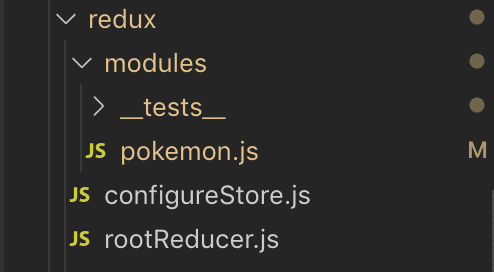

The rootReducer is a file that contains all the reducers used across the app, the configureStore.js file is for setting up the store, it contains the rootReducer and it could also have all the extra middleware, we might want to add. The modules folder contain al the duck modules, we wish(we’re going to talk of them later) and the tests for each of them.

How to write a duck?

Writing a duck module is fairly easy, once you get used to it, you’ll write very fast. Duck structure is the following:

- We write the action types.

- We write the reducer.

- We write the action creators.

- We write side effects if applicable.

It does not sound that hard right? but we have to keep in mind certain rules for writing a duck module:

- We MUST have the reducer as the default import.

- We MUST export its action creators as functions.

- We MUST have action types in the form

app-name/reducer/ACTION_TYPE. - We MAY export its action types as

UPPER_SNAKE_CASE, if we require them somewhere else.

So now that we know how to structure them, let’s write a basic module, we’re going to start writing the action types:

// Actions types

const FETCH_POKEMON_DATA = "pokemon-frontend/pokemon/FETCH_POKEMON_DATA"

const FETCH_POKEMON_SUCCESS = "pokemon-frontend/pokemon/FETCH_POKEMON_SUCCESS"

const FETCH_POKEMON_FAILURE = "pokemon-frontend/pokemon/FETCH_POKEMON_FAILURE"

const RESET_POKEMON_DATA = "pokemon-frontend/pokemon/RESET_POKEMON_DATA"In this case I have four action types that are named using the convention, in this case the app name is called pokemon-frontend, the module name is called pokemon and the action type is written in UPPER_SNAKE_CASE.

After that I like to add the default state for my module, which in this case will be this one:

// Initial State

const initialState = { pokemonList: [], isLoading: false, error: {} }Now we should write a reducer for our state, remember that the reducer is in charge of changing the state by returning a new object based on the action received:

// Reducer

export default function reducer(state = initialState, action = {}) { switch (action.type) {

case FETCH_POKEMON_DATA:

return {

...state,

isLoading: true,

}

case FETCH_POKEMON_SUCCESS:

return {

...state,

pokemonList: action.payload.data,

isLoading: false,

}

case FETCH_POKEMON_FAILURE:

return {

...state,

error: action.payload.response.data,

isLoading: false,

}

case RESET_POKEMON_DATA:

return { ...state, ...initialState }

default:

return state

}

}Keep in mind that the reducer should be the deafult import, and notice that the function receives the state and the action, the reducer is going to check for the action.type attribute and according to that it will return a new state. We use the spread operator to return a new object containing the initial state object which the respective changes. For example if we dispatch the action FETCH_POKEMON_DATA the returned state should be:

store.dispatch({ type: FETCH_POKEMON_DATA })

console.log(store.getState())

/*

Output:

{

pokemonReducer: {

error: {},

isLoading: true,

pokemonList: [],

}

}

*/As you can see on this code snippet, the initialState is not the same anymore cause the loading attribute changed to true, since we called store.dispatch, this triggered the action { type: FETCH_POKEMON_DATA } and that went to look in our reducer to see if the action.type matched with the switch statement case, in this case it did match, and the returned object updated the loading attribute to true.

Pretty cool right, now we have to create the action creators, as I mentioned before, they are just functions that will return an action.

// Action Creators

export function loadPokemon() {

return { type: FETCH_POKEMON_DATA }

}

export function loadPokemonSucceed(payload) {

return { type: FETCH_POKEMON_SUCCESS, payload }

}

export function loadPokemonFailed(payload) {

return { type: FETCH_POKEMON_FAILURE, payload }

}

export function resetPokemon() {

return { type: RESET_POKEMON_DATA }

}So why, should we use them?, since we can call the action itself in the dispatch, as the example I used above to explain the reducer change.

- Helps with abstraction and reduces code, because we don’t have to type the action name everytime, and we reduce the number of imports.

- Understand the code better by having names on the parameters, so you know what exactly does the action needs to have in order to change the state.

A basic example on how can we use them(very similar to the one above, using the action):

const payload = { data: ["Bulbasaur", "Squirtle", "Charmander"] }

store.dispatch(loadPokemonSucceed(payload))

console.log(store.getState())

/*

Output:

{

pokemonReducer: {

error: {},

isLoading: false,

pokemonList: ["Bulbasaur", "Squirtle", "Charmander"],

}

}

*/Now if you want, you can add selectors, or side effects handling, after that, but your module is done. here’s the full snippet:

// Actions types

const FETCH_POKEMON_DATA = "pokemon-frontend/pokemon/FETCH_POKEMON_DATA"

const FETCH_POKEMON_SUCCESS = "pokemon-frontend/pokemon/FETCH_POKEMON_SUCCESS"

const FETCH_POKEMON_FAILURE = "pokemon-frontend/pokemon/FETCH_POKEMON_FAILURE"

const RESET_POKEMON_DATA = "pokemon-frontend/pokemon/RESET_POKEMON_DATA"

const initialState = { pokemonList: [], isLoading: false, error: {} }

// Reducer

export default function reducer(state = initialState, action = {}) {

switch (action.type) {

case FETCH_POKEMON_DATA:

return {

...state,

isLoading: true,

}

case FETCH_POKEMON_SUCCESS:

return {

...state,

pokemonList: action.payload.data,

isLoading: false,

}

case FETCH_POKEMON_FAILURE:

return {

...state,

error: action.payload.response.data,

isLoading: false,

}

case RESET_POKEMON_DATA:

return { ...state, ...initialState }

default:

return state

}

}

// Action Creators

export function loadPokemon() {

return { type: FETCH_POKEMON_DATA }

}

export function loadPokemonSucceed(payload) {

return { type: FETCH_POKEMON_SUCCESS, payload }

}

export function loadPokemonFailed(payload) {

return { type: FETCH_POKEMON_FAILURE, payload }

}

export function resetPokemon() {

return { type: RESET_POKEMON_DATA }

}This is a pretty basic example on how to use redux, with ducks, I explained some of the basics of redux, you should also need to know how to combine reducers, how to setup the store and how to use them with react, maybe I will write a post for it, because I don’t want to make this so long.

I would like to highlight that scoping this through modules using ducks can make the app scalable, easier to read and most importantly, will help begginers to not get confused by other approaches, that normally have the redux boilerplate through lots of folders.

- ← Rails API with a frontend built in React, Part IV.

- Infinite scrolling using redux and sagas, Part I. →

Built and mantained by Jean Aguilar

Nobody likes you when you're twenty three